If Noam Chomsky is the Devil’s Accountant, then Sigmund Freud is the Architect of Dreams. Not the whimsical kind involving rainbows and flying cows, but the kind where you’re chasing your mother through a dark hallway while holding a cigar. And yes, it is just a cigar. Or is it?

Explaining Freud is like trying to explain cricket to an American. At first glance, it’s long, confusing, and seems to revolve around daddy issues. But if you sit with it long enough, you begin to realise the strange beauty of a man who single-handedly turned Western civilisation into a therapy session.

Freud – The Interpreter of Nightmares

Freud didn’t just invent psychoanalysis. He invented the modern notion of the self: that what we are is not just what we do, or say, or post on Instagram, but a bubbling cauldron of instincts, memories, and traumas buried beneath the surface. Born in 1856 in what is now the Czech Republic, Freud was a neurologist by training, but like all true revolutionaries, he broke his field before he built a new one.

What Copernicus did to the Earth, Freud did to the human ego: he displaced it from the centre. His claim? You are not the master of your own house. Your mind is not a palace but a haunted mansion, and the real decisions are made in the basement, by people you’ve never met, in languages you can’t speak.

The Ego, the Id, and the Oh-So-Fraught Superego

Freud’s most enduring contribution is the structural model of the psyche: the id, the ego, and the superego. If the human mind were a dysfunctional family dinner, the id would be the drunk uncle demanding cake, the superego would be the grandmother wagging her finger about cholesterol, and the ego would be the exhausted host trying to keep the peace.

- Id: the primitive, instinctual part of the mind, all hunger, libido, and tantrum.

- Superego: the internalised parent, full of shoulds, musts, and guilt trips.

- Ego: the negotiator, stuck between your inner caveman and your inner priest.

Freud’s model of the psyche is often compared to Plato’s chariot allegory. The id is the wild black horse of passion pulling recklessly, the superego is the white horse of restraint tugging toward virtue, and the ego is the charioteer—struggling to keep both in check while trying not to crash into existential despair.

This model helped Freud explain why civilised people behave in very uncivilised ways—and why your dreams might involve inappropriate thoughts about your chemistry teacher.

Freudian Slips and Other Confessions

Freud was obsessed with the idea that everything we say accidentally is actually on purpose. You didn’t “accidentally” call your boss “mum.” That was your unconscious waving a little flag. These verbal misfires, known as Freudian slips, revealed the darker urges we tried to repress. And repression, for Freud, was the root of neurosis. Forgetfulness, phobias, even physical symptoms—all were expressions of unprocessed trauma lurking beneath consciousness. The mind, he said, was a battleground. And dreams? That was where the war played out.

The Talking Cure and the Couch Revolution

Freud’s great innovation was the couch—not just for naps, but for confessions. He developed psychoanalysis: a method that involved free association, dream interpretation, and long silences where your therapist waits for you to say something meaningful while billing you by the hour.

The “talking cure,” as it was called, wasn’t just about healing. It was about uncovering. Freud believed that to be free, you had to confront what you’d buried. Therapy wasn’t about fixing problems; it was about excavating them.

Freud – The Cultural Prophet

Though he began in medicine, Freud’s impact spilled far beyond psychiatry. His ideas shaped art, literature, feminism, cinema, and even politics. Think of Fight Club and Black Swan, or Hitchcock’s Psycho. Think of advertising’s obsession with desire, or politics’ manipulation of mass psychology. It’s all Freud, baby.

Where Marx saw class conflict and Darwin saw natural selection, Freud saw repression. Civilisation, he argued, was a trade-off. We get security, but we give up freedom. Our lusts are suppressed, our instincts caged, and the result is a society full of frustrated people dreaming of escape.

This was most memorably expressed in Civilisation and Its Discontents, where Freud argued that all of society’s order and beauty is built on top of a reservoir of rage and desire. If Chomsky was the prophet of logic, Freud was the prophet of libido.

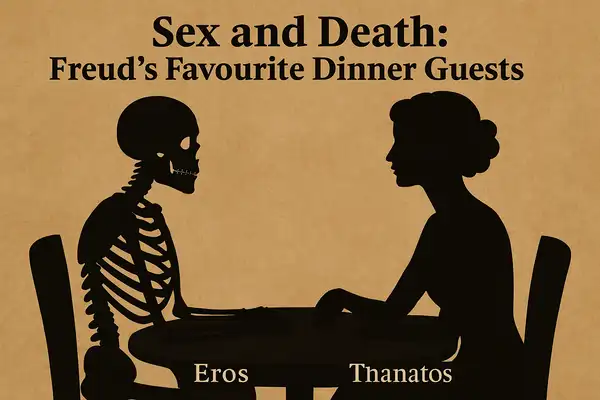

Sex and Death: Freud’s Favourite Dinner Guests

Freud’s theories inevitably return to two things: sex and death. Eros and Thanatos. The life drive and the death drive. He believed human behaviour was driven by the need to create and the urge to destroy. Love and aggression were two sides of the same coin, forever intertwined.

He scandalised Victorian Europe by suggesting that children were sexual beings (cue monocle drop) and that even the most upstanding citizen was full of shameful urges. His theory of the Oedipus complex—that boys experience unconscious sexual desire for their mothers and rivalry with their fathers—was less a literal claim and more a metaphor for how identity is formed through conflict and repression.

Still, it didn’t stop generations of undergraduates from looking at their parents weirdly for weeks after Psych 101.

Freud – The Flawed Genius

Let’s be clear: not everything Freud said has stood the test of time. Some of his theories—like penis envy or the seduction theory—have been widely discredited. Feminists have taken him to task. Neuroscientists have rolled their eyes. And even modern psychologists often treat him like a problematic grandfather: respected, but not to be left alone at parties.

Yet, like Shakespeare or Darwin, Freud’s shadow looms over everything that came after. Carl Jung, Jacques Lacan, Melanie Klein, Slavoj Žižek—they’re all riffing off Freud. Every time someone says “you’re projecting” or jokes about daddy issues, they’re paying homage to him.

Freud’s Final Years

Freud fled the Nazis in 1938 and spent his last days in London, dying a year later of jaw cancer after decades of cigar addiction. He asked for euthanasia, and his doctor obliged. A final act of control from a man obsessed with the things we cannot control.

His ashes are stored in a Grecian urn, which, in an almost too-symbolic twist, was nearly stolen in 2014. Even in death, Freud can’t catch a break from people wanting to steal his essence.

Freud’s Enduring Relevance

We live in a time of TikTok therapy, Instagram trauma, and dopamine detoxes. Freud might scoff at the pseudoscience of it all, but he’d also recognise the yearning beneath it. The desire to be understood. To be free. To turn chaos into meaning. As Chomsky gives us the tools to dissect language and power, Freud gives us the mirror. A cracked one, perhaps, but a mirror nonetheless. As Freud once wrote: “Being entirely honest with oneself is a good exercise.”

In 2025, amid AI hallucinations and algorithmic identities, it might be the best exercise of all.