State-sponsored Iranian hacker group MuddyWater has targeted more than 100 government entities in attacks that deployed version 4 of the Phoenix backdoor.

The threat actor is also known as Static Kitten, Mercury, and Seedworm, and it typically targets government and private organizations in the Middle East region.

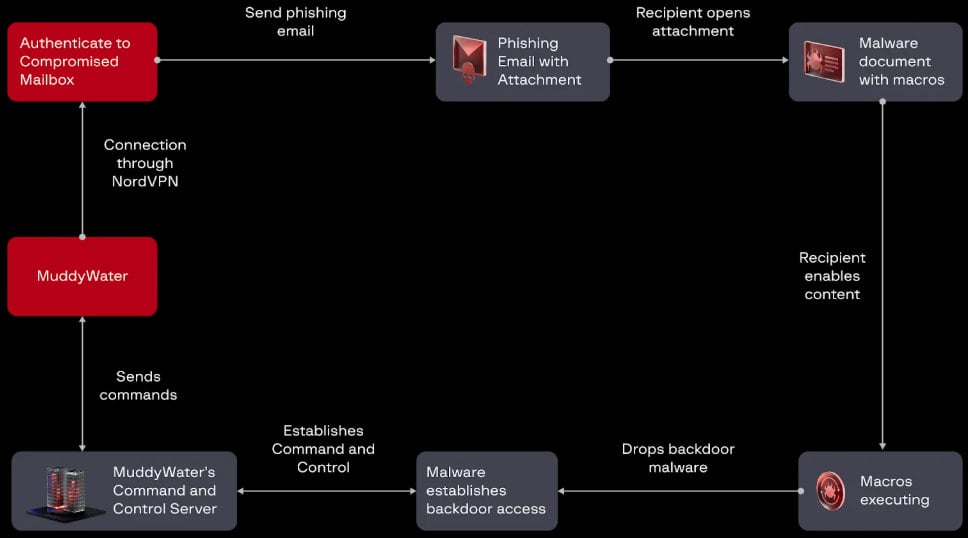

Starting August 19, the hackers launched a phishing campaign from a compromised account that they accessed through the NordVPN service.

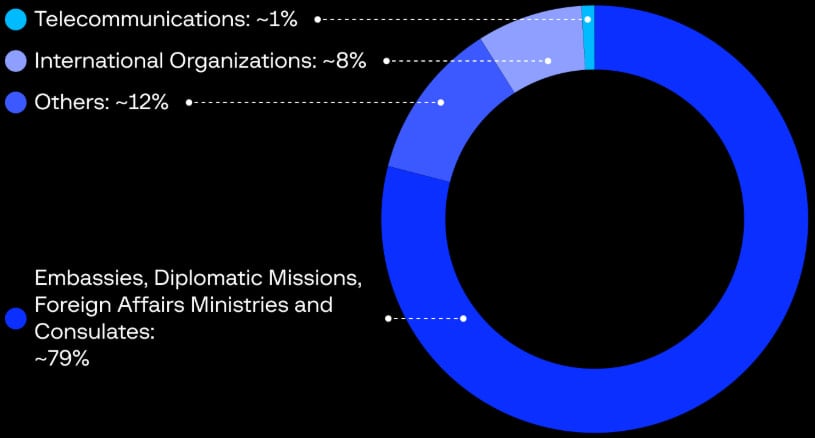

The emails were sent to numerous government and international organizations in the Middle East and North Africa, cybersecurity company Group-IB says in a report today.

According to the researchers, the threat actor took down the server and server-side command-and-control (C2) component on August 24, likely indicating a new stage of the attack that relied on other tools and malware to gather information from compromised systems.

Most of the targets of this MuddyWater campaign are embassies, diplomatic missions, foreign affairs ministries, and consulates.

Source: Group-IB

Back to macro attacks

Group-IB’s research revealed that MuddyWater used emails with malicious Word documents with macro code that decoded and wrote to disk the FakeUpdate malware loader.

The emails attach malicious Word documents that instruct recipients to “enable content” on Microsoft Office. This action triggers a VBA macro that writes the ‘FakeUpdate’ malware loader on the disk.

It is unclear what prompted MuddyWater to deliver malware through macro code hidden in Office documents, since the technique was popular several years ago, when macros ran automatically upon opening a document.

Since Microsoft disabled macros by default, threat actors moved to other methods, a more recent one being ClickFix, also used by MuddyWater in past campaigns.

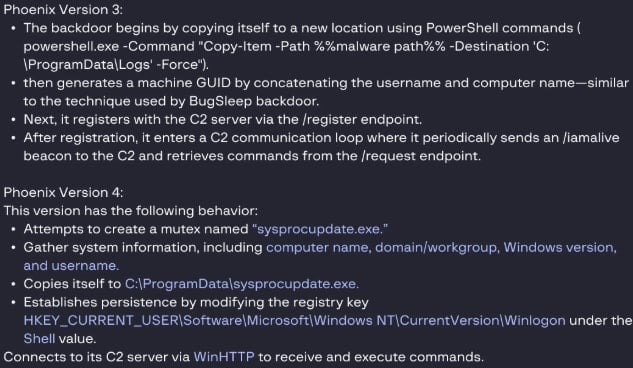

Group-IB researchers say that the loader in MuddyWater’s more recent attacks decrypts the Phoenix backdoor, which is an embedded, AES-encrypted payload.

The malware is written to ‘C:\ProgramData\sysprocupdate.exe,’ and establishes persistence by modifying the Windows Registry entry with configurations for the current user, including the app that should run as the shell after logging into the system.

Source: Group-IB

Phoenix and Chrome stealer

Phoenix backdoor has been documented in past MuddyWater attacks, and the variant used in this campaign, version 4, includes an additional COM-based persistence mechanism and several functional differences.

Source: Group-IB

The malware gathers information about the system, like computer name, domain, Windows version, and username, to profile the victim. It connects to its command-and-control (C2) via WinHTTP and starts to beacon and poll for commands.

Group-IB has confirmed that the following commands are supported in Phoenix v4:

- 65 — Sleep

- 68 — Upload file

- 85 — Download file

- 67 — Start shell

- 83 — Update sleep interval time

Another tool MuddyWater used in these attacks is a custom infostealer that attempts to exfiltrate the database from Chrome, Opera, Brave, and Edge browsers, extract credentials, and snatch the master key to decrypt them.

On MuddyWater’s C2 infrastructure the researchers also found the PDQ utility for software deployment and management, and the Action1 RMM (Remote Monitoring and Management) tool. PDQ has been used in attacks attributed to Iranian hackers.

Group-IB attributes the attacks to MuddyWater with high confidence, based on the use of malware families and macros seen in past campaigns, the use of common string decoding techniques on new malware similar to previously used families, and their specific targeting patterns.